Congenital Scoliosis and Kyphosis

Congenital scoliosis is a curvature of the spine that results from anomalies or abnormally developed vertebrae, the building blocks of the spinal column. These anomalies occur in utero at 4-6 weeks of gestation. Specific abnormalities include hemivertebra, which is a wedge-shaped or half vertebra, unsegmented bar, which is a failure of the normal separation of the individual building blocks of the spine, and mixed abnormalities. The number of abnormal vertebra, their location, and the growth potential around these abnormal vertebrae, is what determines how severe congenital curvature will become. For very mild single vertebra anomalies, a deformity may not be readily apparent and may be picked up incidentally on a chest x-ray or other study done for another purpose. In patients in whom multiple anomalies are noted, the trunk may be severely shortened and severe spinal deformity may be noted. In these cases, the curvature will often progress, resulting in severe lung disease and/or neurological deficits if left untreated.

Patients with congenital scoliosis also have a high incidence of abnormalities in other organ systems. For example, there is a 10% incidence of cardiac abnormalities, a 25% incidence of genito-urinary abnormalities, and up to a 40% incidence of intraspinal anomalies. Therefore, the patients are carefully worked up and even patients, who are seemingly otherwise normal, are sent for testing prior to surgery. Tests performed include an echocardiogram, renal (kidney) ultrasound, and screening MRI of the entire spine. Intraspinal anomalies that can occur include lipomas or fatty benign tumors of the spinal canal, scar tissue within the spinal canal, bony or cartilaginous spicules within the spinal canal, (diastematomyelia) and various other problems. These may require separate treatment from the spinal curvature itself.

The treatment for congenital scoliosis is aggressive in that if progression is noted, even for relatively small curves, surgery is indicated. This turns out to be the most conservative approach in that early surgery often allows the patient to avoid much more extensive surgery later. It is not uncommon for patients of one to one and a half years of age to undergo surgery that is relatively limited in nature. Nonoperative treatment consists of observation at 4 to 6-month intervals and if progression is noted, surgery is indicated. Bracing may be used in only a small percentage of patients in whom compensatory curvatures adjacent to congenital anomalies may be treated to prevent them from worsening.

Surgical intervention is best performed early to minimize the number of levels of the spine requiring treatment. Early surgery includes hemivertebra excision in which the abnormal vertebra is removed allowing the spine to be nearly completely straightened and allowing for the adjacent portions of the spine to grow normally. In more complex congenital anomalies, multiple level fusions may be required both in the front and back of the spine. In other cases, a growth rod procedure may be performed (see article on early onset of scoliosis). The goal is to prevent severe deformities from affecting lung growth or function and to provide comfortable balance of the spine and, in the young child to maximize growth. After surgery, patients are watched carefully until they reach skeletal maturity, which may be as long as 15 or more years following the initial procedure. In some cases, additional curvature arises and may require surgery or bracing. Late presentation of patients with severe curvature and deformity may require osteotomies (cutting through bone) and removal of vertebra and reconstruction of the spine with instrumentation. The goal in these patients is to reestablish spinal balance and alignment and to prevent back pain, neurological deficits, as well as pulmonary lung dysfunction.

A related problem in some patients with congenital scoliosis includes rib abnormalities in which ribs are either missing or fused together. This restricts the growth of the chest cavity and limits lung development, causing potentially severe respiratory compromise. A procedure that has been developed in San Antonio, Texas allows the chest cage (thorax) to be expanded with a special device (Veptr) and may preserve or improve lung function in severely affected patients.

The ideal treatment in patients with congenital scoliosis is early intervention when increasing curvature is noted. The most conservative approach is often early surgery in very young children in order to minimize the number of levels of the spine that require fusion and treatment and to preserve long-term growth of the spine, spinal balance and alignment, and lung function and development.

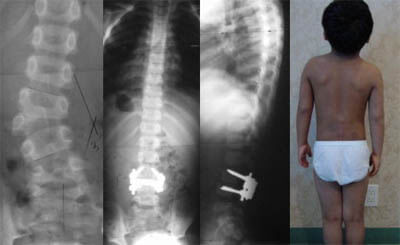

Patient Story 1

This 5 years old boy had progressive scoliosis due to hemivertebra. This was excised by Dr. Lonner and a one level fusion was performed with 100% correction of the scoliosis. He has done very well 10 years following the surgery.

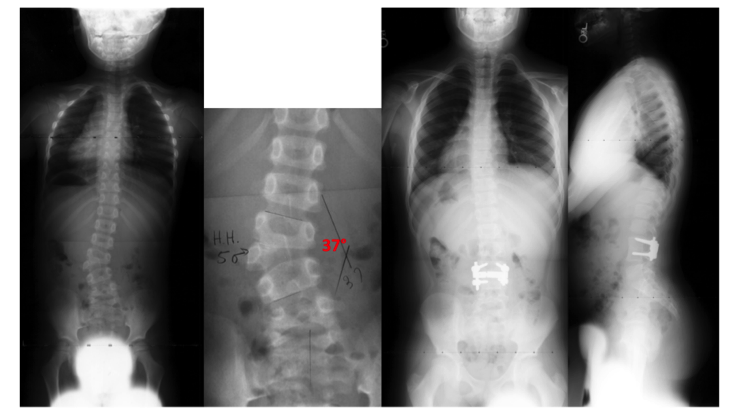

Patient Story 2

This is a 12½ years old boy with a progressive congenital scoliosis due to hemivertebra. He was treated with hemivertebrae excision and spinal fusion by Dr. Lonner with near complete correction of his scoliosis.

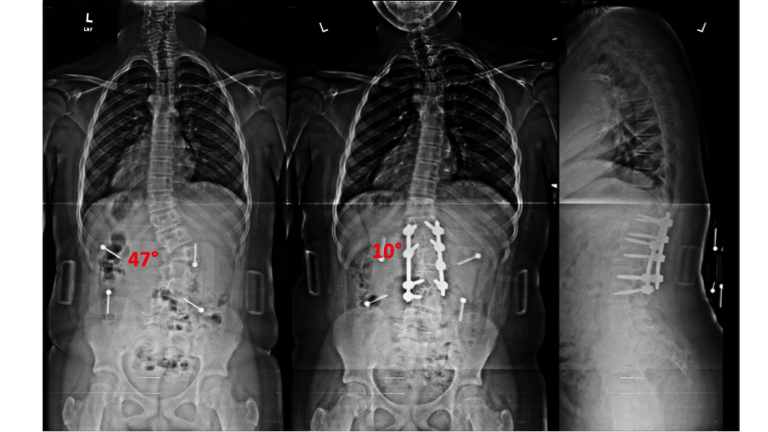

Patient Story 3

This 6 year old female underwent hemivertebrae resection for a progressive congenital scoliosis of 38 degrees. The patient has resumed all her normal activities including ballet classes.

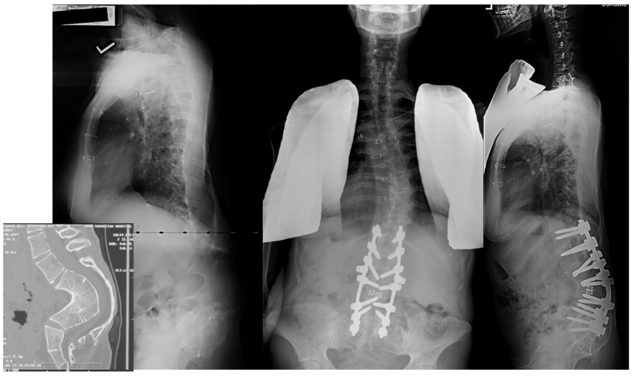

Patient Story 4

This 17-year old young woman has lumbar congenital kyphosis. Her deformity and pain had worsened over time. Dr. Lonner performed vertebral column resection and spinal fusion, which corrected her kyphosis, eliminated her pain and restored her function. She has since been married.